Bonkers

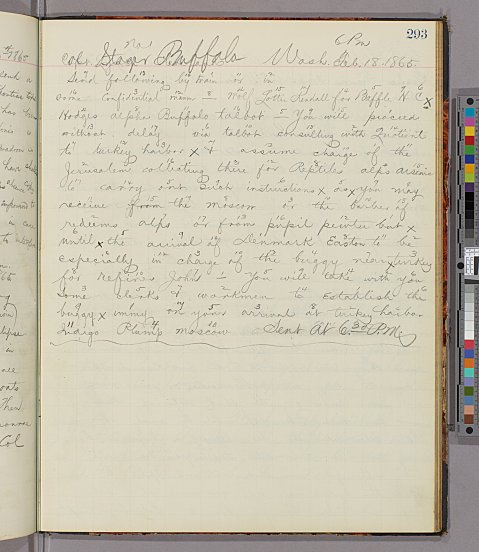

“Bonkers” message. EC 19. Ciphers Sent. 1864, Jan. 27 — 1864, Dec. 2. P. 293.

I’ve often felt that that the vocabulary of archival description could benefit from some content designators. When it comes to ciphered telegraphic messages, the term “bonkers,” as applied to the telegram above, seems very apt.

The USMT cipher men indeed appear to have been on a mission not dissimilar to the staff of the “Confuse-a-Cat” outfit from the Monty Python sketch.

The ciphers were constantly changed, modified, updated, and otherwise fiddled with. The first version of the cipher, developed by Anson Stager for Governor of Ohio in April 1861, was so short that it fit on the back of a business card. The last iteration to be used during the war, cipher No. 4, contained some 1500 arbitraries. The ciphers were numbered out of conventional sequence: the ciphers developed early in the war were numbered 6 and 7, followed by the series of 12, 10, and 9, then 1 and 2, and, towards the end of the war, 3, 4, and 5. These series did not replace each other but rather were often used simultaneously. Occasionally they had to discarded. No. 6 and 7 were discontinued in August 1862, after Nathan Brooks was captured by John H. Morgan’s men, and No. 12 followed suit after Stephen L. Robinson fell to guerrillas in July 1864. The cipher No. 1 which, according to William R. Plum was used to send “more important telegrams,” had to go after James E. Pettit and John F. Ludwig were captured by Forrest’s men in September 1864.

The arbitraries were confusing enough. But there were also the blind or check words, used solely to confuse the interceptor, that could be thrown in either at the end of each column or after every sixth word; commencement words that could indicate the number of either words or lines, and key words concealing different routing techniques for the entire telegram or its parts, coded by columns, numbers assigned to each square made by the column lines, or both.

All these were in constant flux. After he met a “reformed gambler” on a train, Stager updated the routing instructions in cipher No. 12, to include a mnemonic devise revealed by that venerable gentleman. All you had to do was to memorize the formula “K 842 W 795 M 361 B,” or “The King had 842 women, 795 men and 361 boys” and use it to shuffle the deck to know the exact location of every card. The numbers stood for the spotted cards, with 1 designating the ace. “Boys” indicated a ten spot; “Women,” the Queen, and “Men,” for Jack. Stager appropriated the formula, replacing the king, queen, jack, and ten-spot with numbers 13,12,11, and 10, to scramble a message following the sequence 13- 8-4-2-12-7-9-5-11-3-6-1-10. Ciphers No. 9 and 10, adopted for the use of the Western Departments, relied on a further elaborated version of this technique, with each word numbered and counted from the top or of the bottom of a column, with X standing for a check word.

What we see in the “bonkers” message is the process of finalizing a new cipher. The message itself was of no particular importance. As seen from this publication in OR, it merely informed Assistant Quartermaster Captain H.C. Hodges to take charge of Sherman’s supplies.

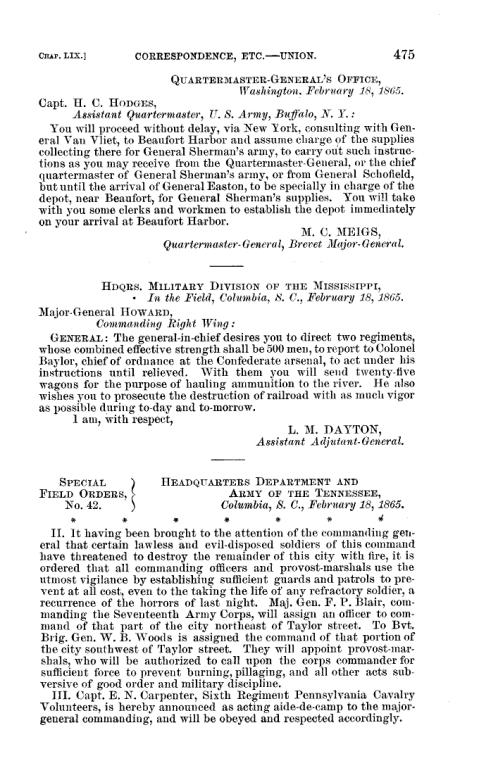

Official Records of the War of the Rebellion. Series 1, vol. 47 (Part 22) P. 475. The “bonkers” message appears at the top of the page.

Stager, Stafford G. Lynch, and other cipher men used this message as a guinea pig for testing various routing instructions being developed for a new cipher. What they were working on was Cipher No. 4, the last cipher to be used during the war. Its predecessor, known as No. 3, was devised by Samuel H. Beckwith in winter of 1864 and included a new set of arbitraries which, among other things, addressed the problem of a “stuck” sounder by avoiding certain letters. (A stuck sounder often resulted in making dashes instead of dots and which, on one memorable occasion turned “pacific” into “fairfye.”) Beckwith’s cipher was unveiled on December 25, 1864 but, for some reason, saw little use.

The top message, first addressed to Stafford G. Lynch, was instead sent to Stager, with the instructions to return it “by train of or in Some confidential manner.” Two different ciphers of the same message were also sent to John Horner in New York.

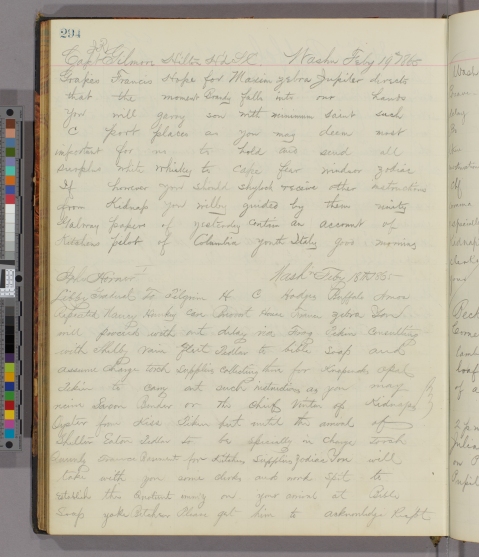

EC 19. Ciphers Sent. 1864, Jan. 27 — 1864, Dec. 2. P. 294. Note a different version of the “bonkers” message, the second on the page.

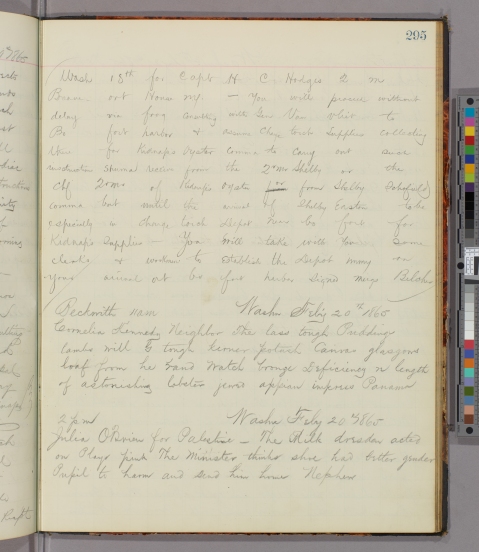

EC 19. Ciphers Sent. 1864, Jan. 27 — 1864, Dec. 2. P. 295. Another version of the “bonkers” message, on the top of this page.

The result of this work was sent to the operators at Grant’s, Sherman’s, and Thomas’s commands on March 23, 1865. The final product, known as Cipher No. 4, numbered some 1608 arbitraries; the key proper comprised 12 pages, each differing in the words used and the route employed. Significantly, the book contained no directions for the use of the cipher; if captured, it was of little use to the anyone who was not a USMT cipher man, including, I am afraid, archivists.

There is one additional takeaway from the story of the “bonkers” message: the fact a message appears in OR certainly does not diminish its historical value.

Olga Tsapina, Norris Foundation Curator of American History. The Huntington Library.

Hi Olga – fascinating as always! I’m sure mine is not an original idea but has anyone ever approached NSA for possible help in solving some of these remaining mysteries (cipher No. 4, etc.)?

have a fun weekend, Craig

LikeLike

Thanks, Craig! We haven’t thought about involving NSA (yet). We’ll see if we can try figure it out on our own. There is an available copy of the No. 4 at VMI, so it’s a start. Olga

LikeLike

Thats the spirit! Craig

LikeLike